Right

from the beginning, the NZ Government’s stream of emails and texts had warned

that visitors to Gallipoli would experience lengthy delays, and urged patience.

Well, they weren’t wrong. A very, very long day – all 29 hours of it – was made

to feel even longer by so much of it spent just waiting. That’s not a

complaint, really, just a fact of life: this is a centenary commemoration, the

first, and a very special occasion, and 10,500 people from NZ and Australia had

come to be part of it. Even our super-efficient Insight Vacations tour director wasn't able to make 6 kilometres of coaches disappear.

We

left our hotel at 5.30pm on the previous day, and struck our first real delay

on the ferry taking us across the Dardanelles to Canakkale. Another ferry from

the British ceremony at Helles, loaded with dignitaries including Princes

Charles and Harry, and various Prime Ministers and ambassadors, was escorted

past us by a flurry of coastguard and police boats as we circled in a holding

pattern. Then it was a slow trip to the first checkpoint where each coach was eventually

boarded by a cheery Australian viewing passes and issuing wristbands; followed

by another slow trip to the next one, ditto, with security screening.

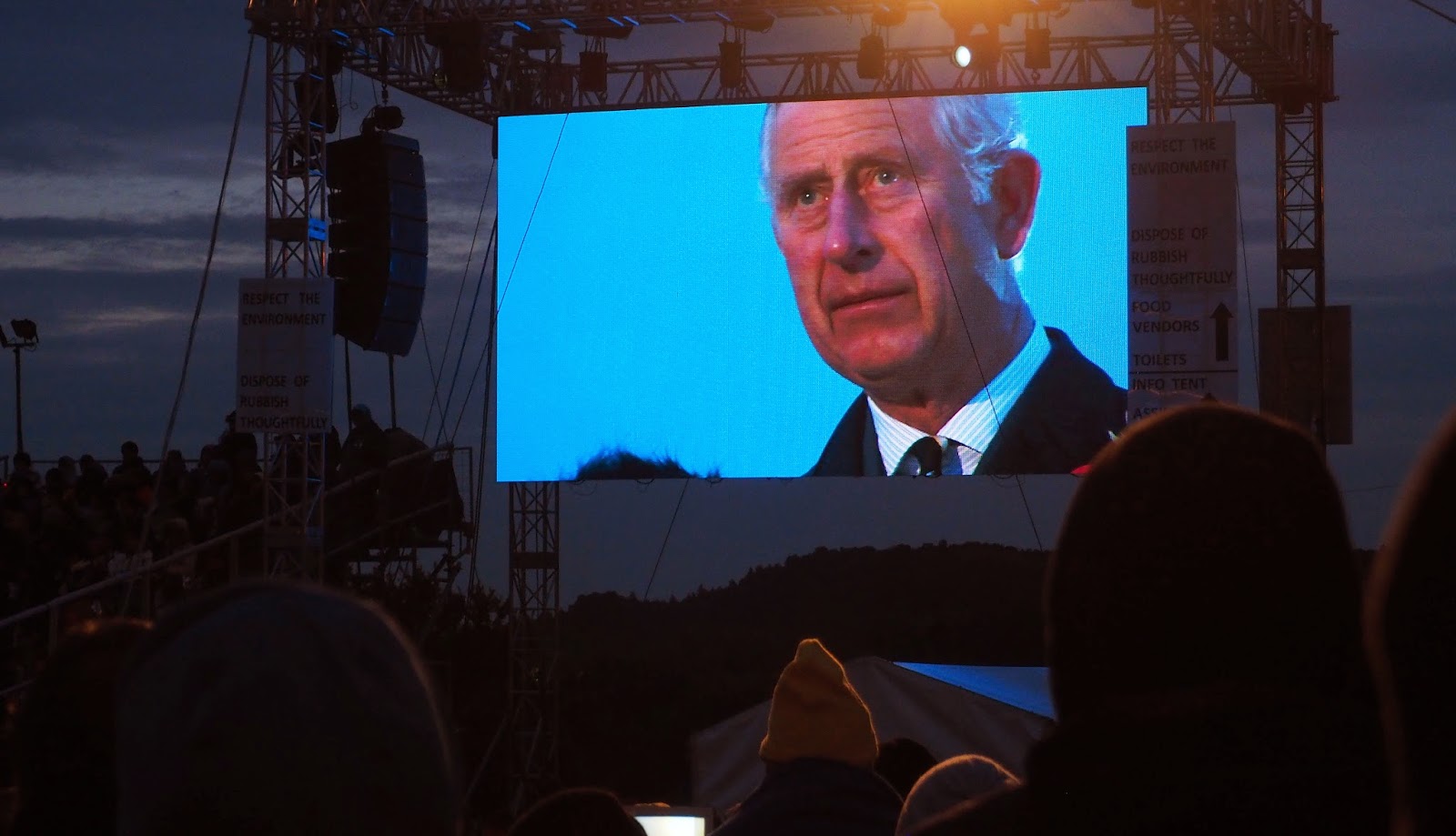

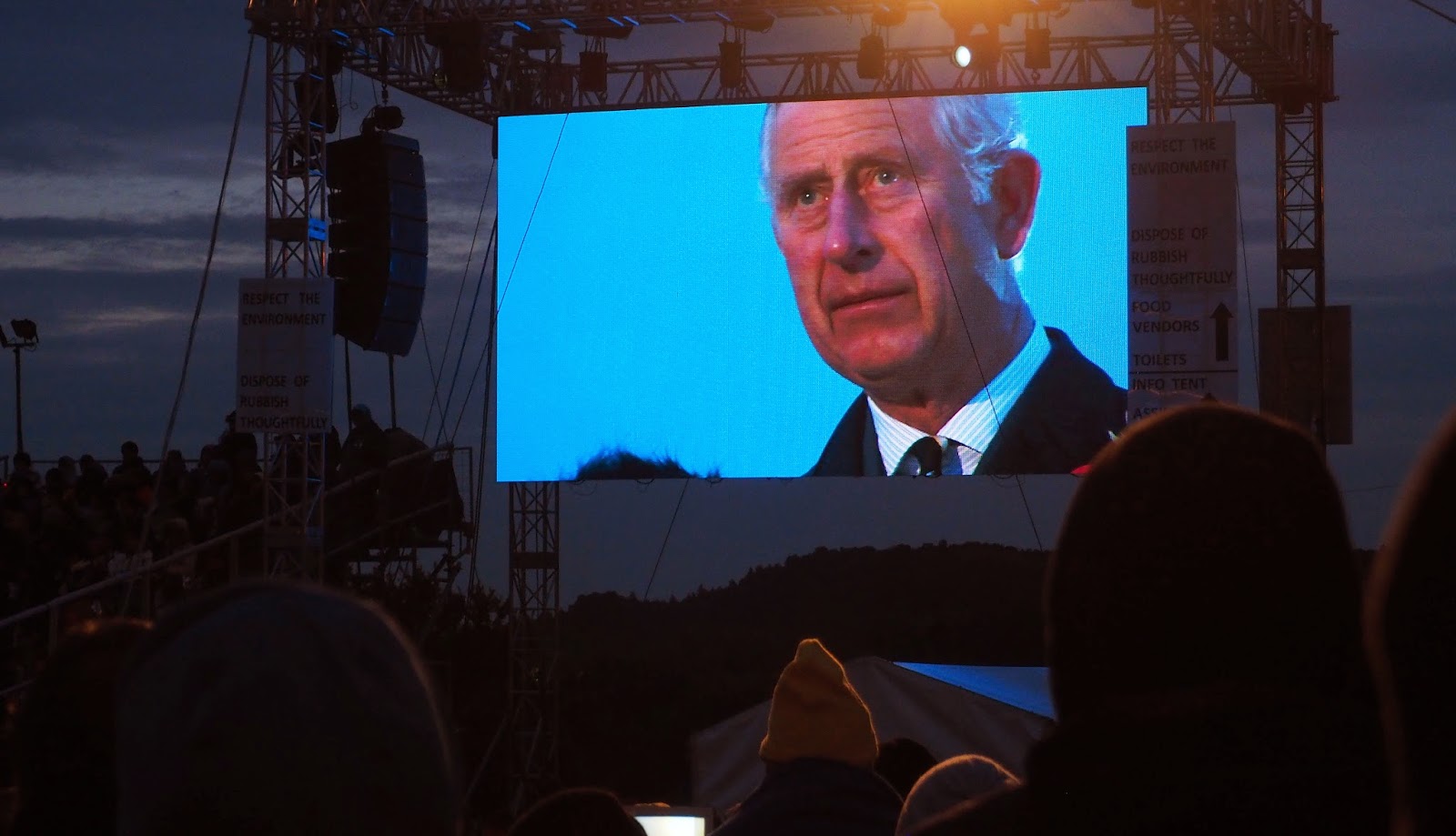

Here

we waited under the pine trees, watching the programme on a big screen while

room was made for us at the Anzac Commemorative Site. After we’d walked a

couple of kilometres along the road and past Anzac Cove to the site, we

understood: a number of those people who’d arrived earlier – by now, dear

reader, it was 2am on Anzac Day, and we were, as the crow flies, really no great distance from our

starting point at Assos – were spread out, fast asleep in

sleeping bags, on the grassed areas that we’d all been repeatedly told had

space for sitting only.

Full

marks to the Aussie MC, though, who via the two giant screens jollied and

cajoled them (once they’d been woken by a few sly kicks from the new arrivals –

oops, sorry, did I wake you?) into making room. We all eventually found a

space, though few of us were able to see down the slope to the centre of

activity, which was disappointing if inevitable given the topography, and most of the time we stood. Those

who’d scored the seats with a view had been there since about 2pm.

So

we sat in the dark, watching on the screens the programme of music and

documentary – well done, that didgeridoo player, especially – and absorbing the

time and place. There were lots of personal touches: letters and epitaphs read, photos flashed up. Every so often we were told what had happened at that moment

100 years before, which was pretty special, and at one point the Sphinx and

other cliffs behind us were lit up while we stood in the dark and listened to

the recorded sound of oars in the water, and real nightingales singing.

The

sky began to lighten, and, at 5.30am, 12 hours after we’d set off, the ceremony

began. It was well done. Our Prime Minister John Key’s speech was good but the Aussies' Tony Abbott’s was too

long and rambling and sent me briefly to sleep. Prince Charles did a reading,

there were letters read by students, there were hymns and prayers, and three

anthems, all sung well, even ours sounding jaunty and un-dirgelike for once.

The Last Post and Reveille were sounded with only one bum note, and then it was

all over.

Was

it special? Yes: to be on the spot where it all happened, exactly 100 years

later, to have visited the cemeteries, stood on the beach, looked at the

gullied cliffs, was special. To be in a crowd that had come so far, who were my

people, who included direct descendants, children of Gallipoli soldiers even, and war veterans, was special. Was it

emotional? No. Perhaps because over the last few days we had heard so many

stories about the battle, had become so familiar with the facts; or maybe

because we were all so tired, having (apart from the selfish sods in the

sleeping bags) had nothing more than snatched moments of sleep all night.

Whatever, no-one I spoke to felt emotional at the Dawn Service, although everybody approved of it. The nearest I

got to a lump in the throat was seeing the silent convoy of naval ships passing by in the background as the sky

lightened and the bagpipes were played, perfectly spaced from the horizon to

the foreground, cruising slowly, respectful.

Last

in, first out. We shuffled away from the site and along the road again, watched

by armed soldiers and hearing skylarks, and set off up Artillery Road, an

unsealed track up the hill to Lone Pine.

Here the Aussies split away for their

service and, after peeling off a few thermal layers (it hadn’t rained or been

seriously cold all night) we carried on another 3km up and down the narrow road

past small cemeteries, past the Turkish memorial to the 57th

Regiment, past the opposing trenches in the pine trees, to Chunuk Bair, where so many died, and we waited. And waited: for the Turks to have their service and for everyone to

arrive. We ate our hotel-supplied breakfasts, and chatted and compared notes,

and watched the Lone Pine service on the screen.

At

1pm we were allowed through from our holding area where the Defence Forces had

been looking after us, and my seat was behind and to the side of the tall

memorial, facing the dignitaries and with a clear view of the Ataturk statue

(its unfinished plinth renovation hidden beneath Turkish flags). We had music

from the band and the Youth Ambassadors, Charles and Harry arrived to press some flesh (“And have you been awake all night?”), all the bigwigs got settled,

a soldier positioned himself with his semi-automatic on the rear platform with

the TV cameras, looking outwards; and the service began.

It

was good. It felt familiar, like family. John Key’s second speech was even

better, Harry did a reading in his remarkably unposh accent, Charles laid a

wreath, there was a solid Maori element, and the Last Post and Rouse, on a 100

year-old bugle engraved with battle names, was perfect.

So,

was it all over? Hardly. We filed back to the marquees and waited another five

hours for our bus to arrive. Five hours! But people were cheerful, the Forces

and especially the MC were focused on maintaining morale (“Anyone feeling sick?

We have a doctor here. Anyone feeling really

sick? We’ve got a chaplain”) and though there was some fading, there was no

real complaining. We were brought hot soup and tea and noodles, and when our

buses finally arrived, there was a corridor of high-fiving Defence people to

walk through. They did a great job.

We

got back to the hotel sometime after 11pm, about 30 hours after we’d left, most

of us having had nothing more than snatches of sleep. Was it worth it? Oh, yes.